Dictionaries

Let's learn about another Python basic (mutable) data type -

dictionary, or short, dict.

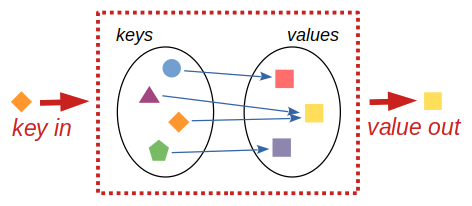

Dictionary is a data structure consisting of multiple key/value pairs, mapping keys to their corresponding values.

Its main purpose is to find quickly and efficiently a value for a given key.

Python constraints what dictionary keys can be. The keys must not repeat (one key cannot map to two different values) and must not be changeable (mutable values, such as lists and dictionaries are therefore not allowed). Strings keys are the most common, though other types such as numbers and tuples are also used.

The target values, as in the case of, e.g., lists, can by anything which can be assigned to a variable. The values can repeat and multiple keys can point to a same value.

Enough abstract talking, let's move to an example. This is a dictionary with 3 keys, and each one of them has a value:

>>> record = {'name': 'Peggy', 'city': 'Prague', 'numbers': [20, 8]}

>>> record

{'name': 'Peggy', 'city': 'Prague', 'numbers': [20, 8]}

Note the curly braces {} and the colons : between each key and value.

The key/value pairs are separated by commas ,.

Are dictionaries ordered? As of Python 3.7 officially (effectively already from Python 3.6) dictionaries are gurateed to preserve order in which their key/values pairs are inserted. Before, the ordering was not guaranteed, as it can be still found mentioned in older text books.

You can get values from the dictionary similar as from lists, but instead of an index, you have to use e key.

>>> record['name']

'Peggy'

If you try to access a non-existent key, Python won't like it:

>>> record['age']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 'age'

You can change the values of keys:

>>> record['numbers'] = [20, 8, 42]

>>> record

{'name': 'Peggy', 'city': 'Prague', 'numbers': [20, 8, 42]}

... or add keys and values:

>>> record['language'] = 'Python'

>>> record

{'name': 'Peggy', 'city': 'Prague', 'numbers': [20, 8, 42], 'language': 'Python'}

... or delete keys and values using the del command (also the same as for lists):

>>> del record['numbers']

>>> record

{'name': 'Peggy', 'city': 'Prague', 'language': 'Python'}

Dictionaries in Python have a couple of useful methods which are good to know.

One of them is the get method which allows you to get a value for a key

when the key exists or return a default value when it does not exist:

>>> record.get('name') # key exits and value is returned

'Peggy'

>>> record.get('age') # key does not exist and None is returned instead

>>> record.get('age', 'n/a') # key does not exist and 'n/a' is returned instead

'n/a'

Sometimes, we use the get method with the same value for the key and the

defaut value which is useful for substitutions (values not found in the

dictionary are passed unchanged, values found in the dictionary are replaced)

>>> values = ["A", "B", None, "D"]

>>> subtitution = {"B": "x", None: " "}

>>> [subtitution.get(field, field) for field in values]

['A', 'x', ' ', 'D'] # note the replaced "B" and None values

The for loop inside square brackets is called list comprehension.

Other useful method is pop, removing key from the dictionary and

returning its value. pop throws an error in case of a missing

value, unless a default value is provided:

>>> record.pop('name') # 'name' is removed from dictionary

'Peggy'

>>> record.pop('name')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 'name'

>>> record.pop('name', None) # None is returned

>>> record.pop('name', 'n/a') # 'n/a' is returned

The setdefault method either returns a value for an existing key or

sets the key to the a default if the key

is missing:

>>> record

{'city': 'Prague'}

>>> record.setdefault('name', 'Lucy')

'Lucy'

>>> record

{'city': 'Prague', 'name': 'Lucy'}

The update method updates a dictionary from another one (rewrites existing

and adds new keys):

>>> record

{'city': 'Prague', 'name': 'Lucy'}

>>> record.update({'name': 'Peggy', 'hobby': 'Python programming'})

'Lucy'

>>> record

{'city': 'Prague', 'name': 'Peggy', 'hobby': 'Python programming'}

Lookup table

A use of dictionaries other than data clustering is the so-called lookup table. It stores values of same type.

This is useful for example with phone book. For every name there is one phone number. Other examples are dictionaries with properties of food, or word translations.

phones = {

'Tyna': '153 85283',

'Lubo': '237 26505',

'Andreea': '385 11223',

'Fabian': '491 88047',

'Vitoria': '491 88047',

'Oliwia': '491 88047',

}

colours = {

'pear': 'green',

'apple': 'red',

'melon': 'green',

'plum': 'purple',

'radish': 'red',

'cabbage': 'green',

'carrot': 'orange',

}

Update Lubo's number to be the same as Fabian's as they now temporarily share phones

Solution

Iteration

When you loop over a dictionary using for, you will get only keys:

>>> func_descript = {'len': 'length', 'str': 'string', 'dict': 'dictionary'}

>>> list(func_descript)

['len', 'str', 'dict']

>>> for key in func_descript:

... print(key)

str

dict

len

If you want to access the values, you will have to use the method values:

>>> list(func_descript.values())

['length', 'string', 'dictionary']

>>> for value in func_descript.values():

... print(value)

string

dictionary

length

But in most cases, you will need both -- keys and values.

For this purpose, dictionaries have the method items.

>>> list(func_descript.items())

[('len', 'length'), ('str', 'string'), ('dict', 'dictionary')]

>>> for key, value func_descript.items():

... print('{}: {}'.format(key, value))

str: string

dict: dictionary

len: length

There is also the method keys() which return just keys.

keys(), values() and items() return special objects

which can be used in for loops (we say that those objects are iterable),

and they may behave as a set.

This is well described in the documentation

In a for loop, you can't add keys to dictionary nor delete them:

>>> for key, value in func_descript.items():

... func_descript[key.upper()] = value.upper()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

RuntimeError: dictionary changed size during iteration

>>> for key in func_descript:

... del func_descript[key]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

RuntimeError: dictionary changed size during iteration

... this limitation can be easily overcome by using a list copy of the iterator

>>> for key, value in list(func_descript.items()):

... func_descript[key.upper()] = value.upper()

>>> func_descript

{'len': 'length', 'str': 'string', 'dict': 'dictionary', 'LEN': 'LENGTH', 'STR': 'STRING', 'DICT': 'DICTIONARY'}

>>> for key in list(func_descript):

... del func_descript[key]

>>> func_descript

{}

However, you can change values for already existing keys.

Update the phones dictionary so that all numbers contain '+43' prefix

Solution

Using a for loop, ensure that following keys are deleted from the dictionary phones.

keys_to_delete = ['Lubo', 'Tyna', 'Oliwia']

Solution

How to create a dictionary

Dictionaries can be created in two ways.

The first way uses curly brackets {}.

>>> {} # empty dictionary

{}

colours = {

'pear': 'green',

'apple': 'red',

'melon': 'green',

'plum': 'purple',

'radish': 'red',

'cabbage': 'green',

'carrot': 'orange',

}

You can fill a new dictionary from one or more existing ones

new_colours = {

**colours, # ** unpacks dictionary into key value pairs

'celery': 'green',

'squash': 'yellow',

'plum': 'purple',

}

Alternatively, you can create dictionaries by dictionary comprehension:

colour_riped = {

key: f'blackish-brownish-{value}'

for key, value in colours.items()

}

The other way to create a dictionary is by using the keyword dict.

This works similar to strings, integer or list, so it will

convert some specific objects to a dictionary.

>>> dict() # empty dictionary

{}

A dictionary has very specific structure -- pairs of values -- numbers or simple lists can't be therefore converted into a dictionary. But we can convert a dictionary into another dictionary (creating a copy). This new dictionary won't change the old one old one:

colour_riped = dict(colours) # make a new dict, a copy of colours

for key in colour_riped:

colour_riped[key] = 'blackish-brownish-' + colour_riped[key]

print(colours['apple'])

print(colour_riped['apple'])

We can also convert a sequence of pairs (e.g., list of tuples) (which work as key and value) into a dictionary:

>>> data = [(1, 'one'), (2, 'two'), (3, 'three')]

>>> dict(data)

{1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

>>> data = [[1, 'one'], [2, 'two'], [3, 'three']]

>>> dict(data)

{1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

... a sequence of pairs can be also generate with the zip function

>>> keys, values = [1, 2, 3], ['one', 'two', 'three']

>>> number_names = dict(zip(keys, values))

{1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

As a bonus function, dict can also work with named arguments.

Each argument's name will be a key and the argument itself will be the value:

>>> dict(len='length', str='string', dict='dictionary')

{'len': 'length', 'str': 'string', 'dict': 'dictionary'}

Be aware that in this case, the keys have to have "pythonic" names –-

they must follow the same rules as other Python variables.

For example, the following strings can't be keys: "def" or "propan-butan".

Dictionaries and variables

Let me introduce you globals() and locals() Python build in functions

returning dictionaries of global and local variables:

global_variable = "TEST"

c = "Good morning!"

def print_variables(message, variables_dict):

print(message)

for key, value in variables_dict.items():

if not key.startswith("_"): # skip hidden variables

print(f"\t{key} = {value}")

def test_scope(a, b):

c = "Hi there!"

print_variables("global variables:", globals())

print_variables("local variables:", locals())

test_scope(1, 0.5)

global variables:

global_variable = TEST

c = Good morning!

print_variables = <function print_variables at 0x7fbe7fad81f0>

test_scope = <function test_scope at 0x7fbe7f9e1e50>

local variables:

a = 1

b = 0.5

c = Hi there!🤔 wait as sec! Python variables are a dictionary?! ... and functions are stored in variables?! Get me out of here!

Dictionaries and function keyword arguments

Dictionaries can be passed to functions as keyword arguments:

>>> def multiply(a, b):

... print(f"{a!r} * {b!r} = {a * b!r}")

>>> multiply(a=2, b=3)

2 * 3 = 6

>>> arguments = {'a': 2, 'b': "o"}

>>> multiply(**arguments)

2 * 'o' = 'oo'

>>>

Keyword arguments can be collected in a function as a dictionary:

>>> def test(*args, **kwargs):

... print("args:", args)

... print("kwargs:", kwargs)

>>> test(1, 2, 3, a="Hi Bob!", b=True)

args: (1, 2, 3)

kwargs: {'a': 'Hi Bob!', 'b': True}Exercise

Let's finish our tasks with the transliteration table.

Task 4

- Modify the code to extract the transliteration table as a dictionary.

- Write function which transliterates a Cyrilic string into the Latin script. Letters not found in the transliteration table should be passed unchanged.

- Use following names to test your script.

CITIES_UA = [

"Київ",

"Чернігів",

"Одеса",

"Львів",

"Полтава",

"Запоріжжя",

"Евпатория",

"Маріуполь",

"Донецьк",

"Миколаїв",

"Ужгород",

"Рівне",

"Луцьк"

]

This is where we finished last time ...

SOURCE_TRANSLITERATION_TABLE_UA_GB = """

а a

б b

в v

г h

ґ g

д d

е e

є ye

ж zh

з z

и ȳ

і i

ї yi

й ĭ

к k

л l

м m

н n

о o

п p

р r

с s

т t

у u

ф f

х kh

ц ts

ч ch

ш sh

щ shch

ь ʼ

ю yu

я ya

’ ˮ

"""

def parse_table(source):

""" Parse string table. """

table = []

for line in source.splitlines():

row = line.split()

if row: # ignore empty lines

table.append(tuple(row))

return table

def add_capitals(table):

""" Add capital letters to the transliteration table. """

new_table = []

for source, transcription in table:

new_table.append(

(source.upper(), transcription.capitalize())

)

return table + new_table

table = parse_table(SOURCE_TRANSLITERATION_TABLE_UA_GB)

table = add_capitals(table)

print(table)

Solution

And that's all for now

If you would like to know all the tricks about dictionaries you can look at (and also print) this cheatsheet.

A complete description can be found here in the Python documentation.